Most people know that the Antarctic Peninsula is one of the most rapidly warming places on earth. But like everywhere else in Antarctica, the length of available temperature data is short â€" most records begin in 1957 (when stations were put in place during the International Geophysical Year); a few start in the late 1940s. This makes the recent rapid warming difficult to evaluate; in general, what’s interesting is how the trend compares with the underlying variability. As anyone who’s been there can tell you, the weather on the Antarctic Peninsula is pretty wild, and this applies to the climate as well: year to year variability is very large. Put another way, the noise level is high, and discerning the signal requires more data than is available from the instrumental temperature record. This is where ice cores come in handy â€" they provide a much longer record, and allow us to evaluate the recent changes in a more complete context.

A new paper in Nature this week presents results from an ice core drilled by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) at James Ross Island on the Antarctic Peninsula. Before discussing the results, congratulations are due to Rob Mulvaney and his team for obtaining the ice core in the first place, quite apart from the analyses. James Ross Island is a gorgeous place to work on a sunny summer day, but it can be brutal on a bad day, and the BAS team spent many months in the field. The record they obtained is some 50,000 years long â€" by far the longest record ever obtained on the Antarctic Peninsula. (James Ross Island’s ice cap was originally cored by a Argentine/French team back in the 1980s, but they obtained just a 400 year record).

Figure 1.The glaciated summit of Mt. Haddington, site of a new ice core record reported by Mulvaney et al., as viewed from Santa Marta Cove, James Ross Island, on a nice summer day. (photo: E. Steig).

So do Mulvaney et al.’s results allow us to discern signal from noise? The short answer is yes, but it’s not that simple. This is quite apparent from the reporting on the paper, most of which has been pretty accurate, yet with headlines running the gamut from saying that the cause of recent warning is “unclear†(NPR) or “part of longer trend†(Australian Broadcasting Corp.), to “most warming in Antarctic is human caused†(Climate Central) and a more subdued “ususual but not unique†from the BBC.

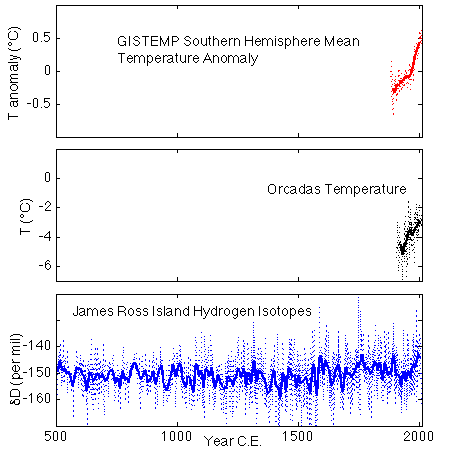

Figure 2. Temperature anomalies averaged over the Southern Hemisphere (top), temperatures from the sub-Antarctic station Orcadas (middle), and hydrogen isotopes (a proxy for temperature) from James Ross Island on the Antarctic Peninsula (bottom).

Why the ambiguity? After all, the results show that it’s now warmer on James Ross Island now than it has been at any time during at least the last millennium (see Figure 2), and its unequivocal that this recent warmth led to the demise of ice shelves in the area over the last few decades. Moreover, the rate of recent century-scale warming is at the upper limit of rates in the pre-anthropogenic era: Mulvaney et al. find that the most recent warming is faster than 99.7% of any other given 100-year period in the last 2000 years. Why then, doesn’t this lead simply to the conclusion that this that recent warming and associated ice shelf collapse and glacier acceleration on the Antartic Pensinula is the result of human activities?

Well, as we’ve noted on many previous occasions, attribution of climate change to specific causes is not simply a matter of looking at whether a particular year or decade is “exceptional†or not. Mulvaney and coauthors have been careful, both in their paper and in interviews about it, to avoid the suggestion that their results are any sort of “smoking gun†pointing towards an anthropogenic cause of the recent warming trend on the Antarctica Peninsula. As I tried to make clear in my News&Views commentary that accompanies their paper, I largely agree. Century scale warming trends comparable to that of the last century have happened before, without any influence from humans, and if we didn’t have any data other than this one ice core, we really couldn’t say much more than that.

What’s missing from this argument, of course, is that we do have other data. For one thing, recent rapid warming in Antarctica isn’t limited to the Peninsula. Whatever you may have read in some quarters, the borehole temperature data from WAIS Divide show definitively that West Antarctica is warming too â€" and in recent decades at least, the rate has been comparable to that on the Peninsula. More importantly, warming is occurring on the Peninsula at the same time that most of rest of the planet is warming. As the figure illustrates, in the Southern Hemisphere that warming has been nearly monotonic since about 1920, whether one is talking about the Southern Hemisphere as a whole (top panel of the figure), at James Ross Island (bottom panel), or at Orcadas in the South Orkney Islands, the one and only location south of 60°S that has a century long instrumental temperature record. This makes it much harder to argue that it is merely “local variability†that explains the recent warming trends. The James Ross Island results thus add yet one more bit of evidence to what we already knew: global warming is.. well, global.

Certainly, this is not the last word. A fly in the ointment here is that at least part of the most recent warming trend may be anthropogenic, yet not due to greenhouse gases in the troposphere. As many studies have argued (see e.g. the review by Thompson et al.), the stratospheric ozone hole has caused changes in the winds around Antarctica, and one of the consequences appears to be advection of warm air from the north onto the Antarctic Peninsula, especially on the east side (where James Ross Island is) during summer. Of course, the ozone hole didn’t exist before the 1970s, so it clearly can’t be invoked for the warming since the 1920s, but any formal attribution study will need to take this, as well as “global warmingâ€, into account.

Mulvaney et al.’s paper doesn’t claim to be an attribution study; it’s largely just reporting the data, which is entirely appropriate. And nor am I suggesting that the simple comparison I’ve made above is any sort of formal attribution study either. Only one formal attribution study has been done for Antarctica that I’m aware of â€" that of Gillett et al., 2008 â€" and that was before any of the recent results showing warming in West Antarctica, and doesn’t including any of the longer term data from ice cores. What’s needed now is an updated study, taking into account all the available data, including that from ice cores. I would very much like to see someone take this on. Including the new results from James Ross Island will be an important part of such work.

No comments:

Post a Comment