Scientists predict ocean temperatures will rise in the equatorial Pacific by the end of the century, wreaking havoc on coral reef ecosystems.

But a new study shows that climate change could cause ocean currents to operate in a way that mitigates warming near a handful of islands right on the equator.

Those islands include some of the 33 coral atolls that form the nation of Kiribati. This low-lying country is at risk from sea-level rise caused by global warming.

Surprisingly, these Pacific islands within two degrees north and south of the equator may become isolated climate change refuges for corals and fish.

"The finding that there may be refuges in the tropics where local circulation features buffer the trend of rising sea surface temperature has important implications for the survival of coral reef systems," said David Garrison, program director in the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the research.

Here's how it could happen, according to the study by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientists Kristopher Karnauskas and Anne Cohen, published today in the journal Nature Climate Change.

At the equator, trade winds push a surface current from east to west.

About 100 to 200 meters below, a swift countercurrent develops, flowing in the opposite direction.

This, the Equatorial Undercurrent (EUC), is cooler and rich in nutrients. When it hits an island, like a rock in a river, water is deflected upward on an island's western flank.

This upwelling process brings cooler water and nutrients to the sunlit surface, creating localized areas where tiny marine plants and corals flourish.

On color-enhanced satellite maps showing measurements of global ocean chlorophyll levels, these productive patches of ocean stand out as bright green or red spots--for example, around the Galapagos Islands in the Eastern Pacific.

But as you gaze west, chlorophyll levels fade like a comet tail, giving scientists little reason to look closely at scattered low-lying coral atolls in that direction.

These islands are easy to overlook because they are tiny, remote, and lie at the far left edge of standard global satellite maps that place continents in the center.

Karnauskas, a climate scientist, was working with coral scientist Cohen to explore how climate change would affect central equatorial Pacific reefs.

When he changed the map view on his screen in order to view the entire tropical Pacific at once, he saw that chlorophyll concentrations jumped up again exactly at the Gilbert Islands on the equator.

Coral reefs near the island nation of Kiribati may be somewhat protected from global warming.

(Photo Credit: NOAA)

Satellite maps also showed cooler sea surface temperatures on the west sides of these islands, part of Kiribati.

"I've been studying the tropical Pacific Ocean for most of my career, and I had never noticed that," he said. "It jumped out at me immediately, and I thought, 'there's probably a story there.'"

So Karnauskas and Cohen began to investigate how the EUC would affect the equatorial islands' reef ecosystems, starting with global climate models that simulate effects in a warming world.

Global-scale climate models predict that ocean temperatures will rise nearly 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) in the central tropical Pacific.

Warmer waters often cause corals to bleach, a process in which they lose the tiny symbiotic algae that live in them and provide vital nutrition.

Bleaching has been a major cause of coral mortality and loss of coral reef area during the last 30 years.

Even the best global models, with their planet-scale views and lower resolution, cannot predict conditions in areas as small as these small islands, Karnauskas said.

So the scientists combined global models with a fine-scale regional model to focus on much smaller areas around minuscule islands scattered along the equator.

To accommodate the trillions of calculations needed for such small-area resolution, they used the new high-performance computer cluster at WHOI called "Scylla."

"Global models predict significant temperature increases in the central tropical Pacific over the next few decades, but in truth conditions can be highly variable across and around a coral reef island," Cohen said.

"To predict what the coral reef will experience in global climate change, we have to use high-resolution models, not global models."

The model predicts that as air temperatures rise and equatorial trade winds weaken, the Pacific surface current will also weaken by 15 percent by the end of the century.

The then-weaker surface current will impose less friction and drag on the EUC, so this deeper current will strengthen by 14 percent.

"Our model suggests that the amount of upwelling will actually increase by about 50 percent around these islands and reduce the rate of warming waters around them by about 0.7 C (1.25 F) per century," Karnauskas said.

Colorful species inhabit equatorial Pacific reefs; these reefs may be global warming refuges.

(Photo Credit: NOAA)

A handful of coral atolls on the equator, some as small as 4 square kilometers (1.54 square miles) in area, may not seem like much.

But Karnauskas' and Cohen's results say that waters on the western sides of the islands will warm more slowly than at islands 2 degrees, or 138 miles, north and south of the equator that are not in the path of the EUC.

That gives the Gilbert Islands a significant advantage over neighboring reef systems.

"While the mitigating effect of a strengthened Equatorial Undercurrent will not spare corals the perhaps-inevitable warming expected for this region, the warming rate will be slower around these equatorial islands," Karnauskas said.

"This may allow corals and their symbiotic algae a better chance to adapt and survive."

If the model holds true, even if neighboring reefs are hard-hit, equatorial island coral reefs may survive to produce larvae of corals and other reef species.

Like a seed bank for the future, they might be a source of new corals and other species that could re-colonize damaged reefs.

"The globe is warming, but there are things going on underfoot that will slow that warming for certain parts of certain coral reef islands," said Cohen.

"These little islands in the middle of the ocean can counteract global trends and have a big effect on their own future," Karnauskas said, "which I think is a beautiful concept."

Tiny dots in a seemingly endless sea, the islands of Kiribati are seen from space.

(Photo Credit: NASA)

Lebanese photographer Roger Moukarzel swapped his warm studio in Beirut for the frozen mountains of Lulea in northern Sweden. He was here to create a series of striking images that would highlight the cause and effect of climate change.

Lebanese photographer Roger Moukarzel swapped his warm studio in Beirut for the frozen mountains of Lulea in northern Sweden. He was here to create a series of striking images that would highlight the cause and effect of climate change.  Lulea is part of the area commonly known as Lapland, a reindeer heartland and home, of course, to Santa Clause's legendary workshop.

Lulea is part of the area commonly known as Lapland, a reindeer heartland and home, of course, to Santa Clause's legendary workshop.  The reindeer share the region with the Sami, Europe's northernmost officially indigenous people, whose ancestral lands spread across Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia.

The reindeer share the region with the Sami, Europe's northernmost officially indigenous people, whose ancestral lands spread across Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia.  Lulea's subarctic climate, with mild summers and long, cold and snowy winters, make it an ideal habitat for reindeer. However, in recent years, locals have said that temperatures have been rising appreciably and, in 2010, a herd of more than 300 reindeer was reportedly lost when the ice cover of a frozen lake broke beneath their hoofs.

Lulea's subarctic climate, with mild summers and long, cold and snowy winters, make it an ideal habitat for reindeer. However, in recent years, locals have said that temperatures have been rising appreciably and, in 2010, a herd of more than 300 reindeer was reportedly lost when the ice cover of a frozen lake broke beneath their hoofs.  Moukarzel takes a picture of a local Sami girl, against the dark, ethereal backdrop of the Lulea forest.

Moukarzel takes a picture of a local Sami girl, against the dark, ethereal backdrop of the Lulea forest.  Dressed in their rich and colourful traditional clothing, Moukarzel positioned his subjects against the intentionally incongruous image of a large, smoke-chugging factory.

Dressed in their rich and colourful traditional clothing, Moukarzel positioned his subjects against the intentionally incongruous image of a large, smoke-chugging factory.

According to Moukarzel, this series of images will be the beginning of many. The 45-year-old photographer plans to travel across all five continents, exploring this theme among different climates and cultures.

According to Moukarzel, this series of images will be the beginning of many. The 45-year-old photographer plans to travel across all five continents, exploring this theme among different climates and cultures.  It will certainly not his first big adventure. At just 15, Moukarzel started his career with moving, sometimes haunting pictures of the Lebanese civil war.

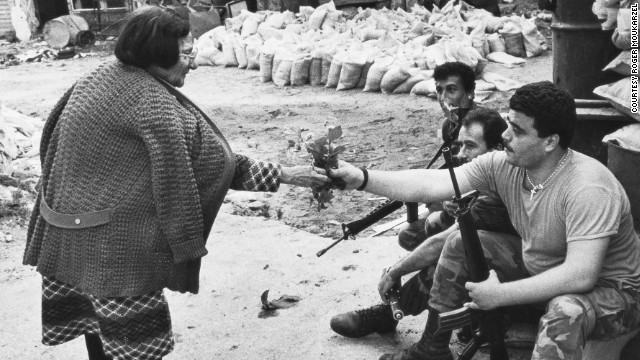

It will certainly not his first big adventure. At just 15, Moukarzel started his career with moving, sometimes haunting pictures of the Lebanese civil war.  He says he has always been primarily interested in taking pictures of people and "capturing moments of humanity" -- such as this striking exchange from 1978 between a Lebanese soldier and a woman in war-torn Beirut.

He says he has always been primarily interested in taking pictures of people and "capturing moments of humanity" -- such as this striking exchange from 1978 between a Lebanese soldier and a woman in war-torn Beirut.  After 15 years as a front-line photojournalist for news agencies Sygma and Reuters, Moukarzel hung up his hard hat in favor of high fashion, as he embarked on a new career in the world of fashion photography.

After 15 years as a front-line photojournalist for news agencies Sygma and Reuters, Moukarzel hung up his hard hat in favor of high fashion, as he embarked on a new career in the world of fashion photography.